[ by Charles Cameron — Lao Tzu with a quick boost from CS Lewis — Tao, Logos and a line of water can be traced across the face of North America ]

.

I have long been an admirer of Lao Tzu, and in particular of the opening phrases of the Tao Te Ching, which Stephen Mitchell renders thus:

The tao that can be told

is not the eternal Tao

The name that can be named

is not the eternal Name.

Lao Tzu, of course, is working within a language that’s impressionistic enough to allow each word multiple resonant connotatations, and English translations of his work are correspondingly very many and varied, as we shall see.

Ursula le Guin translates those same lines:

The way you can go

isn’t the real way.

The name you can say

isn’t the real name.

We can phrase Lao Tzu’s opening lines simply thus:

The way that can be described isn’t the Way:

The name that can be pronounced isn’t the Name.

As an aside, Le Guin lets the cat out of the bag a bout “true names” in her marvelous book, Wizard of Earthsea, in which she writes:

Years and distances, stars and candles, water and wind and wizardry, the craft in a man’s hand and the wisdom in a tree’s root: they all arise together. My name, and yours, and the true name of the sun, or a spring of water, or an unborn child, all are syllables of the great word that is very slowly spoken by the shining of the stars. There is no other power. No other name.

But it’s the Way rather than the Name — not that the two can be anything other than two ways to name the One — which concerns me here, because one of the first DoubleQuotes I’m consciously aware of formulating matched Lao Tzu’s:

The way that can be described isn’t the Way

with Alfred Korzybski‘s central insight in Science and Sanity:

The map is not the territory.

That’s what I was suggesting in the illustration I’ve put at the head of this post, which dates back to the early seventies, several decades before I began developing the HipBone Games, let alone the DoubleQuotes format I now use…

**

All of which would be one of those treasures I keep stashed in my heart (“where neither moth nor rust doth corrupt, and where thieves do not break through nor steal”) — except that the other day I stumbled on a CS Lewis quote that sheds considerable new light on Lao Tzu’s dictum:

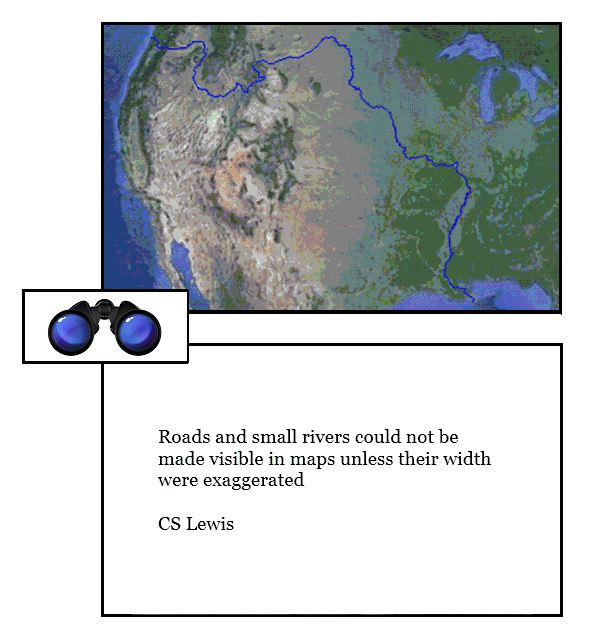

That CS Lewis quote comes from New Learning and New Ignorance, an essay Scott Shipman generously introduced me to the other day. It’s the Introduction to one of his works of literary-histporical criticism, English Literature in the Sixteenth Century Excluding Drama! And in his simple, elegant formulation —

roads and small rivers could not be made visible in maps unless their width were exaggerated

— we have an explanation of one way in which the map must indeed distort the territory if it is to be of any use, one way in which the Way cannot be shoehorned into words.

**

Which brings us to the river whose width is exaggerated, just as Lewis said it would be, in the aerial photo of the continental US that I’ve placed in the DoubleQuote panel directly above the Lewis quote.

It seems [t]his creek divides the US connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, to quote the title of Jesus Diaz’ fascinating article from which that image comes:

The Panama Canal is not the only water line connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. There’s a place in Wyoming—deep in the Teton Wilderness Area of the Bridger-Teton National Forest—in which a creek splits in two. Like the canal, this creek connects the two oceans dividing North America in two parts. [ … ]

The creek divides into two similar flows at a place called the Parting of the Waters … To the East, the creek flows “3,488 miles (5,613 km) to the Atlantic Ocean via Atlantic Creek and the Yellowstone, Missouri and Mississippi Rivers.” To the West, it flows “1,353 miles (2,177 km) to the Pacific Ocean via Pacific Creek and the Snake and Columbia Rivers.”

I’m not often impressed by matters of scale, but that hits my sweet spot. And it seems that fish don’t need to worry about the Panama canal and the political complexities attendant on it —

it is thought that this was the pass that provided the immigration route for Cutthroat Trout to migrate from the Snake River (Pacific) to Yellowstone River (Atlantic) drainages.

All of which fits nicely with the title of one of Alan Watts‘ books: Tao: the Watercourse Way

**

In that book, incidentally, Watts — himself an Anglican priest as well as a long time Zen practitioner — has an interesting observation about the Tao:

Weiger gives Tao the basic meaning “to go ahead.” One could also think of it as intelligent rhythm. Various translators have called it the Way, Reason, Providence, the Logos, and even God…

Thomas Merton, in Zen and the Birds of Appetite, picks up the thread, telling us:

Dr. Wu is not afraid to admit theat he brought Zen, Taoism and Confucianism with him into Christianity. In fact in his well-known Chinese translation of the New Testament he opens the Gospel of St. John with the words, “In the beginning was the Tao.”

And here we’re back to CS Lewis, who wrote in a letter to Clyde Kirby, editor of A Mind Awake: An Anthology of C. S. Lewis and author of The Christian World of C. S. Lewis:

is not the Tao the Word Himself, considered from a particular point of view?

There are times when a network of ideas is so close-woven as to form an intricate virtual conversationa, a bead game, even.

**

Appendix: further readings

You have been very kind to follow me thus far, but while I’m at it I’d like to drop in some readings for those who might like to engage in further exploration of Lao Tzu.

175+ Translations of Chapter 1

These include Wade-Giles & Pinyin Romanizations, plus translations and interpretations by, among others, John Chalmers (1868), James Legge (1891), D.T. Suzuki and Paul Carus (1913), Aleister Crowley (1918), Dwight Goddard (1919), Arthur Waley (1934), John C.H. Wu (1939), Lin Yutang (1942), Witter Bynner (1944), D.C. Lau (1963, 1989), Wing-Tsit Chan (1963), Timothy Leary (1966), Peter A. Boodberg (1968), Gia-fu Feng and Jane English (1972), Stephen Mitchell (1988), Thomas Cleary (1991), Ursula K. Le Guin (1998), and Jonathan Star (2001)…

Peter Boodberg’s Philological Notes on Chapter One of The Lao Tzu

These are remarkable, if for no other reason than for giving us the phrase “Myriad Mottlings’ mother”. His versiom of the opening — in what he descibes as having “little literary merit” while reflecting “to the best of my ability, every significant etymological and grammatical feature, including every double entendre, that I have been able to discover in the original”. Boodberg’s whole paper is somewhat stunning — here are the two opening lines:

Lodehead lodehead-brooking : no forewonted lodehead;

Namecall namecall-brooking : no forewonted namecall.

Comments on the Tao Te Ching using the D.C. Lau translation (Penguin Books, 1963):

Verse 1 [see Chinese text and literal translation]: “The Way that can be spoken of/ Is not the constant way.” The Tao Te Ching begins with a pun: “Way” and “spoken of” (“said”) are the same character (Dào). So the first line says: “The Tao that can be tao-ed is not the constant Tao.” “The name that can be named…” Here the pun can be maintained in English, where “name” can be both noun and verb. The quality of a translation of the Tao Te Ching can usually be determined from the rendering of these lines. Those determined to unpack the meaning of Taoism in the translation, according to their own interpretation of Taoist doctrine, will often render these terse sentences into a paragraph, sometimes with irrecognizable renderings of the key words. The affection of a translator for Taoism cannot excuse a method that only obscures the nature of the text itself.

**

Hey, I think of those first two verses of the Lao Tzu as a “pattern” in the Christopher Alexander sense, with Korzybski’s version and CS Lewis additional insight featuring as examplars of the more general principle. I thought I’d do a quick search and wind up with some of my own playful uses of those two phrases in different situations and for different audiences / readerships:

The pronounceable name isn’t the unpronounceable name. The flow that can be capped isn’t the overflowing flow. The quantity that can be counted is not the unaccountable quality. The verbal formulation of x is not the x itself. No way the way can be put into words. The problem that can be described isn’t our actual situation. The describable aint it. More I grasp you, baby, more you disappear…

and not to put too fine a point on it…

the way that can be mapped is not the way to go, the meaning that can be put into words is not the final word

Thank you so much, Charles for sharing your insight.